January 2009

When Richard II confiscated the inheritance of the exiled Henry Bolingbroke in 1399, Henry returned to England, ostensibly to reclaim his inheritance, but in reality to attempt to seize the throne itself. And as Dr Peter Fleming of the University of the West of England revealed on 13th January when he delivered a lecture to the Thornbury Local History and Archaeology Society, the West Country played a key role in the coup d’état which marked the start of the Wars of the Roses.

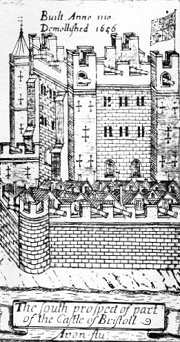

Richard was on campaign in Ireland when Henry landed at Ravenspur in Yorkshire. In the king’s absence he swept through England, gaining a significant foothold and winning substantial poplar support. Richard was expected to return from Ireland via south Wales, and to re-enter England at Bristol, where the castle (located where Castle Park is today) was in the hands of his supporters Bushey, Green, Russell, and the Earl of Wiltshire. The custodians of the castle hoped that Bristol would form a bridgehead from which the king could re-establish control of the country.

It was therefore strategically important that Henry attempted to seize the castle before Richard could reach it. At Berkeley he was joined by Thomas Berkeley, one of the most powerful nobles in Gloucestershire, and by Richard’s uncle, the Duke of York, whom Richard had appointed Regent in his absence. The Duke seems to have sensed which way the wind was blowing, and thrown in his lot with the winning side. From Berkeley the usurping forces marched on Bristol, which they reached on 20th July.

The castle was quite possibly strong enough to withstand a direct assault. Instead, Henry tried a different tactic: Henry Percy, the Earl of Northumberland proclaimed safe passage for those who elected to leave the castle peaceably; all others would be beheaded. When the garrison abandoned the castle in droves to take advantage of this offer, the king’s supporters had little choice but to surrender. Bushey, Green, and Wiltshire were beheaded. Perhaps, it is just as well that they were: had they been allowed to escape, reported the chronicler Walsingham, the townsfolk would have torn them to pieces anyway.

A further example of this antipathy to Richard II can be seen in the events of January 1400. Henry Bolingbroke had acceded to the throne as Henry IV, but his rule was threatened almost immediately by the Epiphany Rising. The plot failed, and the lead conspirators, the Earls of Kent, Salisbury, and Gloucester, fled to Cirencester.

The townsmen cornered the conspiring nobs, and a fight ensued between the earls and the townspeople. The earls were forced to surrender and might have made it out alive, had it not been for the actions of a priest in the earls’ retinue, who set fire to some of the houses in an attempt to create an opportunity for the earls to slip away in the ensuing commotion. Not your average country vicar. The townspeople prevented the escape of the Earls of Kent and Salisbury, whom they beheaded. The heads were sent to the king, who had clearly been wanting a pair of ornamental heads for quite some time, as he generously allowed the townspeople to keep the valuables of the executed earls. Either that, or he realised that there was absolutely no chance of getting them back from the devious residents of Cirencester. The loot seems to have been fairly substantial, as it allowed the townspeople to fund the building of the tower of the parish church of St John the Baptist.

The Earl of Gloucester, Thomas le Despenser, escaped the town and attempted to flee to Cardiff. Unfortunately for him he had been lured into a trap: once out in the Bristol Channel the ship he was travelling aboard changed course for Bristol, and armed troops, who had hitherto been secreted in the hold, emerged on deck to seize him. In Bristol the townspeople clamoured for his death and, despite the best efforts of the Mayor to save him, he was beheaded. His head was sent to London and was displayed on London Bridge until his mother, evidently a forceful woman, demand its return.

Within a few months of these happenings, however, opinion had turned against Henry. The court rolls of the Exchequer and King’s Bench record that a party of women went on the rampage through Bristol and tried to behead the royal tax collector. Sounds like a fairly average Friday night in the city centre.... Again Bristol’s Mayor (by this time presumably pretty frazzled and fed up of his unruly residents) intervened and broke up the mob.

How can we explain this animosity to Richard II, and the city’s abrupt volte face so shortly after the coronation of Henry IV? The motive, predictably, was money. Bristol was second only to London as a provider of credit to Richard II. If the king was insisting on having loans advanced to him, then failing to make repayments, this may go some way to explain the attitude of the Bristolians. (The great Florentine banking family, the Medici, would never, as a matter of policy, loan money to the royal houses of Europe: kings and princes were far too willing to default on their loans, and there was little that their creditors could do about it.) A further reason may be that Richard’s campaigns in Ireland had often led to trade sanctions, disrupting commercial activity with one of Bristol’s main trading partners.

A third factor may be the influence of the Berkeleys, who had traditionally been the most powerful family in Gloucestershire. They were resentful of the rise of the Despenser family, who were closely associated with Richard, and who had been elevated by him to the earldom of Gloucester. And across the country as a whole, Richard’s increasingly erratic behaviour, including ever heavier taxation, made him deeply unpopular.

As for Henry, by September 1399 he had already despatched a royal commission to Bristol to enquire into the whereabouts of what he regarded as his property. The castle had evidently been ransacked after its fall, and its contents “liberated”. A similar enquiry was launched in 1400 relating to the Earl of Gloucester’s possessions. Bristol’s mayors and sheriffs were summoned before the Court of Exchequer, and juries of the townsfolk were judicially interrogated concerning the fate of the missing property. The Bristolians were seemingly unwilling to tolerate these persistent royal enquiries, but this was not the direct cause of the hostility to Henry IV.

On 15th September 1399, Henry had granted remission of tonnage and poundage (customs duties). Three months later he was demanding payment of the duties which had fallen due before his promise was made: a misunderstanding, or ambiguous wording, had led to the assumption on the part of the townspeople that all duties due, past and future, had been forgone by the king. And despite another promise Henry had made, that there would be no taxation during peacetime, taxes remained heavy. This slippery manoeuvring, combined with the fact that Henry, too, saw Bristol as a convenient source of credit, and that Bristol was a hotbed of the heresy known as Lollardy, seems to explain to a large extent the ill feeling towards the king on the part of the people of Bristol.

So Bristol, at the turn of the fifteenth century was far from being an unimportant provincial port. It had played a key role in the deposition of one king, and seemed determined to be a thorn in the side of his successor.

The next meeting of the Thornbury Local History and Archaeology Society will be on 10th February 2009, when Linda Hall will address the Society on the subject of Gloucestershire Farm Buildings.

The Thornbury Local History and Archaeology Society always welcomes new and occasional members. Details of our programme can be found on this website, the library or the Town Hall. Our meetings are on the second Tuesday of the month, held at St Mary's Church Hall beginning at 7.30pm. Visitors are always welcome at the society for the small charge of £3.50